Zanzibar is a beautiful archipelago off the Eastern coast of Tanzania. It comprises an island which is also called Zanzibar, which hosts a city which is also called… you got it. “Zanzibar” means “coast of the Black (people)”, in Persian and in Arabic, and this name is indicative of its history. If you sail south from the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf, hugging the Eastern coast of Africa, at a certain point you are bound to arrive at these islands and their convenient ports. For Arabs, Iranians and Indians, Zanzibar and the surrounding area represented a gateway to the interior of Africa, and for the people of the interior of Africa, it was an outlet to the Indian Ocean world. Soon a mixed culture developed, based on Islam, a network of trading cities, and the use of Swahili (a Bantu language with many Arabic loanwords).

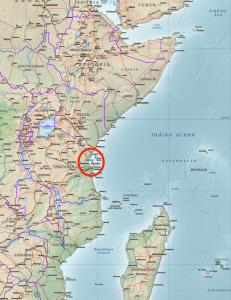

Location of Zanzibar on the East African coast (image from Wikimedia, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/99/Map_of_Africa_%28physical%2C_political%2C_population%29_with_legend.jpg)

In the nineteenth century this region was ruled by the Sultanate of Zanzibar. It controlled many slave routes, through which it moved captives from inside Africa to the Middle East. It also exported to the rest of the world products such as copal (a kind of resin) or cloves. What did the Zanzibari élite, and the Swahili people more generally, do with the money they obtained in return?

Jeremy Prestholdt answered this question in Domesticating the World: African Consumerism and the Genealogies of Globalization (University of California Press 2008). The title of the book shows its approach, which analyzes how Zanzibaris appropriated and re-semanticized the consumption of foreign goods, in order to build their identities and express their worldview. To put it simply, Zanzibaris consumed certain things because they found them cool, and Prestholdts studied how and why Zanzibaris came to think that way. In the nineteenth century, they bought all kinds of things from abroad, like umbrellas and clocks, glasswork and pieces of furniture. Their consumption was so massive that it had a profound impact on areas on the other side of the world, and actually helped their industrial development.

Among the goods that the Swahili people imported, a special place was held by a particular kind of unbleached cotton cloth. It had a somewhat grayish color, but it could be dyed or printed with different patterns, and modified through the insertion of borders, edges, or stripes of other cloth, to suit all kinds of taste. It was so widespread that it came to be used as a unit of value: all over Eastern Africa, people measured goods in terms of how much cloth they were worth. Its Swahili name, “merikani”, is a clear hint of its origin.

People wearing merikani cloth, in Zanzibar (from this website dedicated to Zanzibar history, https://zanzibarhistory.org/amerikani_clothing_in_zanzibar.htm)

Merikani was originally a product of Massachusetts. Local businessmen had found that Swahili people really liked their products, and that their demand was apparently inexhaustible: even when they did not consume their cloth themselves, they re-exported it to even more eager buyers in the interior. The very first fully steam-powered textile factory in the Western Hemisphere, Pequot Mills in Salem, was built in 1847 to keep up with rising African requests. Of course many competitors tried to dent American predominance, but to no avail. Even England, the homeland of the Industrial Revolution, the “factory of the world”, and the main naval power of the Indian Ocean, had to accept that its products ranked only second in the preferences of Swahili consumers.

The success of Massachusetts factories, however, was based on the supply of good, cheap cotton from the US South. When the Civil War broke out, their looms were suddenly cut off from their providers of raw material by thousands of kilometers of bloody front lines. Nevertheless, the Zanzibaris were still eager to buy merikani cloth, and this created a big market opportunity. Manchester mills thought they finally stood a chance. In the end, however, English producers had to give up again to other competitors, who enjoyed a closer supply of cotton and lower operating costs, and who also happened to be one of their own colonies.

The new rising star in East African cotton trade was actually Bombay, not Manchester. India, of course, had always been a big producer, if not the main producer of cotton textiles in the world. As it is well known, however, its artisanal manufacture had been severely disrupted by the competition of British industrial goods. By 1850, India was apparently doomed to be only a provider of raw cotton for British factories. Still, all was not lost: even back then there were enough local investors, and local technicians, to try to set up European-style factories, and to beat the British at their own game. They could enjoy much lower labor costs, but they also profited from an extensive Indian mercantile presence, which spread all the way from the Red Sea to Mozambique. Indian traders were profoundly embedded in local societies, and knew exactly what their prospective buyers were looking for. Indian businessmen started with a rather low profile, modifying English cloth that they re-exported to East Africa, but soon their activity rose to massive proportions: by 1888 Bombay exported 15 billion yards of cloth to Zanzibar, that is, one third more of what the Americans had sold there in their best times.

Of course Bombay, massive as it is, was, and still is, just a small part of India: the industrialization of the whole subcontinent took many more decades, and is still an ongoing process. However, the road was set, and Zanzibari demand played a huge role in building it. If you now take a look at your shirt, and find a label which says “Made in India” (or “Made in Bangladesh” or “Made in Pakistan”, as those countries were also part of British India at the time), remember that its history goes back a long way in the past: not just to some enterprising businessmen or technicians from Gujarat or Maharashtra, but also to many demanding African customers from Zanzibar.

References

Jeremy Prestholdt, Domesticating the World: African Consumerism and the Genealogies of Globalization, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2008

William Clarence-Smith, The Textile Industry of Eastern Africa in the Longue Durée, in Emmanuel Akyeampong, Robert H. Bates, Nathan Nunn, James Robinson (edited by), Africa’s Development in Historical Perspective, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2014, 264-294.

Ryan Mackenzie Moon, Converging Trades and New Technologies: the Emergence of Kanga Textiles on the Swahili Coast in the Late Nineteenth Century, in Pedro Machado, Sarah Fee, and Gwyn Campbell (edited by), Textile trades, consumer cultures, and the material worlds of the Indian ocean: an ocean of cloth, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, pp. 253-286