The history of the production and commerce of trade guns in the second half of the 19th century evokes an African centrality that most existing accounts of the growth of international economic integration have tended to obscure from view and reminds us that a focus on African consumer demand might be of some value to understand the workings, not only of specific economic sectors, but of modern globalization as well. It is therefore right to start this journey with the analysis of one of the products studied during our research.

Flintlock firing mechanisms first appeared during the 16th century, with the definitive “true flintlock” being developed in France in the early 17th century. The invention is typically attributed to Marin le Bourgeoys, a gunsmith from Normandy. Le Bourgeoys’s groundbreaking design quickly established itself as the standard for flintlocks, rapidly replacing most older firing mechanisms across Europe.

Transcending geographical boundaries and temporal contexts, the exportation of flintlocks extended to various regions of Africa in the 19th century, including the lower Congo area. Throughout the initial eighty years of the century, the Congo estuary remained entirely beyond the reach of European political dominion. Economically, this region remained a significant entity, forming a crucial segment of the ‘free’ coast, situated between the protectionist Portuguese Angola to the south and the protectionist French Gabon to the north.

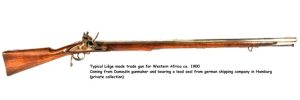

Throughout this period of intense commercial interaction, consumers in the lower Congo consistently favoured flintlock muzzle-loading muskets, often referred to as “trade” or “African” guns, and earlier as “slave” guns. The preference for flintlocks over percussion locks stemmed from the frequent scarcity of the caps needed for the latter, whereas flintstones were abundant. The diversity of models documented in existing gun-maker catalogues, along with practices such as the addition of specific decorations and logos, suggests that European manufacturers made considerable efforts to accommodate the evolving preferences of African consumers.

In terms of functionality, flintlocks, given their limited penetrative power, are unlikely ever to have proved very effective in big-game hunting. However, their military applications were significant, especially since the dense mangrove swamps and natural canals allowed gunmen familiar with the terrain to approach enemies undetected.

Additionally, imported firearms, like other externally introduced technologies, carried symbolic attributes that resonated with the socio-cultural norms and structures of the local communities.

With the beginning of Belgian colonization, the introduction of so-called “improved” weapons was strictly limited. The firearms permit was instituted in 1899 and its regulations were clarified in 1901. Due to fraud, the Colonial Government in 1903 meticulously specified the regulations: the introduction and sale of weapons were prohibited, except for those intended for the military and the police, or with exceptional individual authorization. All improved weapons and their ammunition had to be registered within three months, and African holders of any firearm were required to declare and stamp their weapon. Only the importation, sale, transport, and possession of common powders, known as “trade powders,” and unrifled flintlock guns, that is, the old model predating 1842, flint or cap-lock, could be authorized by the General Commissioner.

The Protocol signed in Brussels on July 22, 1908, for an initial period of four years starting from February 15, 1909, definitively prohibited “the importation, sale, and possession of weapons intended for indigenous use.”

References:

Coquery-Vidrovitch, C. Le Congo au temps des grandes compagnies concessionnaires, 1898-1930. Paris: Editions de l’Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, 2002.

Macola, G. The Gun in Central Africa: A History of Technology and Politics. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2016.

Kinard, J. Pistols. An Illustrated History of Their Impact. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2004

Macola, G. Nineteenth-century ‘trade guns’ in the Congo Estuary: Local refractions of a global trade. Journal of Global History. Published online 2025: 1-15: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-global-history/article/nineteenthcentury-trade-guns-in-the-congo-estuary-local-refractions-of-a-global-trade/2EB3482791F1EE78E743D62300A3F003

Post by Mariella Terzoli