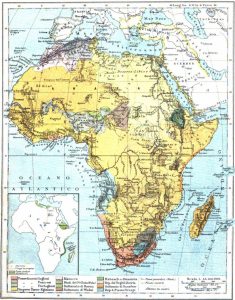

At the end of the issue of “L’Esploratore” from January 1882, after 48 black-and-white pages, readers found a colour map of Africa, updated to the last geographical discoveries:

Nowadays, we are probably struck at first sight by its colours. There are many areas that are painted with only slightly different hues, and it is sometimes difficult to tell apart the different political entities they represent. The background colour is yellow: yet, the north-eastern part of Africa has a slighlty lighter yellow, in order to identify the “Turkish-Egyptian Empire” (a definition that was also ambiguous, as Egypt, nominally an Ottoman province, was for all practical purposes an independent state, and managed its empire with precious little Turkish involvement). A bit to the south, yellow gives way to a pale orange strip: that’s the sultanate of Zanzibar which ruled over the Swahili coast, more or less where nowadays Kenya and Zanzibar are. Further to the south, the blue used for the sea blends into the blue used for the Portuguese colonies, such as Mozambique. All the other colours (green, pink, grey, green) have pale and sometimes similar hues.

As regards physical geography, it’s quite an accurate map. Of course, there are some mistakes here and there, but the basic structure of the continent is the same you can find now in every atlas: the Nile flowing from Ethiopia on one side and Lake Victoria on the other, the long and narrow lakes of the Rift Valley, the distinctive curved shapes of the Congo, Niger, and Zambesi rivers…

By contrast, the political situation depicted on this map refers to a very specific historical moment. Try and recall, from your history classes, the maps that showed the European “Scramble for Africa”: a collection of colonies with very straight borders, with a long strip of British possessions in the East, the Belgian Congo in the middle, the French all around the place… This map shows a completely different picture.

To be sure, there are a few colonies: the key identifies British, French, and Portuguese territories, which can be found on the map. You can spot some British pink in South Africa, some more on the Gold Coast (nowadays Ghana), further north Algeria is already French… but most of the rest is under no European domination at all. A large part of Africa is just a huge yellow blob, painted only with the background colour – partly out of sheer ignorance, and partly out of a Eurocentric prejudice that it was not worth the effort to tell the different African polities apart. However, there are some states which are singled out, such as the age-old empires of Morocco or Ethiopia, or the lesser known sultanates of Bornu and Wadai (the green and brown spots south of the Sahara, more or less where now Chad is). All these countries are identified on the key of the map, on the same level of the European possessions.

This map photographs the very last moment in which Africa can be represented this way. Let’s move to the top right. Egypt, as we mentioned, was basically an independent state, with its own army, its own navy… and alas, its own public debt. Egypt had been for a few years on the brink of bankruptcy, and as its creditors were Europeans, European states started to concern themselves with the Egyptian budget. The situation was volatile, and in the summer of 1882, that is, just a few months after the publication of this map, the British bombed Alexandria and occupied the whole country. They left the Egyptian administration in place, but they put it under their supervision. Egypt, while still nominally an Ottoman province, had turned from an independent state into a British colony.

Other parts of Africa followed suit. On the far left of the map, that small grey area is the French colony of Senegal. In the following years, the French would expand it eastwards, until it merged with their other possessions in Gabon and Algeria. Meanwhile, on the mouth of the Congo river, the Belgian King Leopold II was busy establishing a private colony of his own. The official aim was to “spread civilisation” and collect rubber, and the end result was the death of millions of Congolese people who happened to be on the way. The Portuguese expanded their frontiers, the Germans jumped in, the different European states scrambled to get the richest colonies before the others.

“L’Esploratore” and its readers would also be part of this process. On the left of the page, you can see a smaller map of Africa with some green areas: those are the “countries studied and explored” by the society that published the magazine. These green spots had no political meaning: “L’Esploratore” had described the Zanzibari trade, but nobody expected the Italian navy to go and conquer Zanzibar because of that. Yet, the general assumption was that Italian traders would operate in those areas, and link them to their own country. People thought about commercial connections, economic influence, imagined some kind of what would now be called “soft power”. Some even proposed to establish a few outposts here and there, showing the Italian flag over a few warehouses, or maybe fantasized about sponsoring Italian emigration in the area…

It was all very vague, but there was a clear direction. In ten years’ time, “L’Esploratore” would publish maps of Africa that showed, among the others, also some Italian possessions, and people discussed how to make them larger and larger. The time of “influences” was over, and the time of outright military conquest had begun.