Nineteenth-century European colonialism was a complicated process. It involved armies and missionary societies, merchants, politicians, and adventurers; however, a small but significant role was also played by learned societies, which produced, gathered, and distributed geographical knowledge. Some of these associations were specifically devoted to “commercial geography”, and businessmen financed them in the hope that they would get useful economic information: where there was gold, where there was cotton, where you might exchange your products in exchange for silver coins or ivory tusks… This was also the case with the Society of Commercial Exploration in Africa (Società d’Esplorazione Commerciale in Africa, or SESCA), which was founded in Milan on 2nd February 1879.

Back then, the Kingdom of Italy had only recently been unified. It was still a comparatively poor country, but its élite had the ambition to turn it into a great power, and the few industries which it possessed were looking for new avenues of investment. The SESCA was born in this context, when a group of people chipped in to organize a commercial expedition to Ethiopia. Some of the investors were just nationalists who wanted to contribute to what they perceived as a worthy cause, but there were also people like the chemical industrialists Carlo Erba and Giovanni Battista Pirelli, who were looking for sources of products such as tamarind and rubber (the Pirelli company is still one of the main producers of car tyres in the world), or winemakers and distilleries which looked for new consumers. The greatest proportion, however, was composed of textile producers, of silk and (mostly) cotton cloth, who comprised more than a third of the individual investors. The cotton industry was a young and weak activity in Italy, which faced a lot of foreign competition: might it escape it in the new, untapped markets in the interior of Africa?

The short answer is: heck, no. The people who lived in the interior of Africa were much less naïve and secluded from the world than they appeared from the lecture halls of Milan. When they produced and used their own textiles, these were hard to imitate in an effective and yet cheap way, and when they imported them from abroad, the Italians faced the competition of producers from the US or India, Britain or France, or even Austria-Hungary or Japan. In the end, the export of cotton cloth to Africa played a negligible role in the Italian industrialization, and the SESCA, by and large, did not foster Italian economic growth.

It was not for lack of trying, however. The SESCA financed the trips of several explorers, who researched market conditions in different places in Africa. “I want to touch, feel and measure everything myself, otherwise I will not trust it” wrote one of them, Gustavo Bianchi, who spent almost three years traveling around Ethiopia, taking notes of what was bought, sold, produced, and required. In 1880 the SESCA also doubled as a commercial company, the Italian Society for the Trade with Africa (Società Italiana di Commercio con l’Africa), which set up a few trading stations: it was wound up a couple of years later, but some of its factors remained on the spot, and set up trading companies of their own. It also experimented with different strategies: many of its members promoted, especially at first, a “peaceful” economic penetration, which would not imply a political domination in Africa. Others, however, promoted a much more aggressive strategy, in the Horn of Africa and Libya: this was the road eventually taken by the Italian state.

Quite soon the SESCA acquired a monthly magazine, “L’Esploratore”, later renamed “L’esplorazione Commerciale”. The reports sent by its explorers were published there, in a more or less abridged version, along with summaries and translations of descriptions of other voyages, economic and political news, debates, and so on. The magazine was clearly aimed at a broad diffusion, and it featured a lot of maps, engravings, and even photographs of the lands it described.

The pages of “L’Esploratore” offer an unparalleled view over the mental world of late-nineteenth century merchants and empire-builders. They also provide a lot of information on African trade in this period, even though one has to take into account the Eurocentric and proto-colonialist bias that it showed: whenever some product was low in demand, its writers tended to attribute that to the congenital “laziness” or “barbarity” of African people, who were however “greedy” and “rapacious” when they desired something, “fraudulent” when they made business, and so on… This magazine shows how Europeans reacted to African demand, and to the requirements it posed to Italian (and European) industry, on the eve of colonial expansion and immediately afterwards.

You have to sell a lot of cotton handkerchiefs, to recoup the expense of more than 200 millions, which is the cost of the [Third Anglo–]Ashanti War. Let us also do some similar calculations, and see if the rising Italian industries can benefit from all these new geographical discoveries. Pisan and Ligurian merchants used to roam across Africa before the Arabs and the Portuguese, and maybe had even come to know the routes recently detected by Cameron and Stanley. Should we let other nations be alone there in looking for profit and glory? (Attilio Brunialti, “L’Esploratore”, 1879)

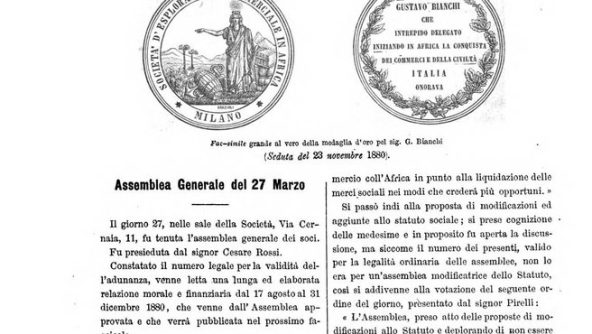

Model of a golden medal that the SESCA gave to Gustavo Bianchi (the guy who wanted to touch and measure everything), for “having started the conquest of trade and civilization in Africa, to the honor of Italy”. In a rather anonymous landscape, which only the presence of a couple of palms identifies as Africa, barrels of goods are slowly piling up. The image is representative of the abstract nature of the continent in the minds of the society administrators, even though Bianchi showed a much more acute attention to details in his own notes.

References

Anna Milanini Kémény, La Società d’Esplorazione Commerciale in Africa e la politica coloniale (1879-1914), Firenze, La Nuova Italia, 1973

Roberto Romano, L’industria cotoniera lombarda dall’Unità al 1914, Milano, Banca Commerciale Italiana, 1992

Gianluca Podestà, Sviluppo industriale e colonialismo: gli investimenti italiani in Africa Orientale (1869-1897), Milano, Giuffré, 1996

Daniele Natili, Un programma coloniale. La Società Geografica Italiana e l’origine dell’espansione in Etiopia, Roma, Gangemi, 2008