For our project, we had to study how Italian colonial authorities described the market for textiles in the Horn of Africa, and how they tried to shape it for their purposes. How can we do that? Most of the relevant documents have survived, but finding them is not necessarily easy.

All administrations produce documents, and the Italians, famous for their cumbersome bureaucracy, were no exception: when an Eritrean askari died in Somalia and his money had to be repatriated to his family, or when port authorities in Assab registered the arrival of a caravan coming from the hinterland, this process created a long series of documents: some of them remained in Africa, but most eventually found their way to Rome, where they were stored in the archives of the relevant ministry: usually, until 1912, that was the Foreign Office, and then the brand-new Minister of the Colonies.

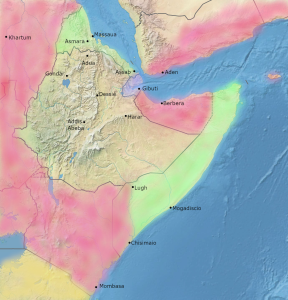

Archives can be organized in many different ways. Most archives now follow the so-called principle of the original order: documents are divided on the basis of which office produced them. So if, for example, colonial authorities set up three trading agencies in independent Ethiopia, in Gondar, Adwa and Dessie, with the aim to promote Italian trade in the area, we should have three different records, one produced by each agency. However, until relatively recent times, it was common to mix up the documents on the basis of the topic they addressed: in this case, we would have all the papers related to the expenses of setting up the agencies in one folder, all the collections of statistical data in another, all the communications with Ethiopian authorities in another, and so on… Organizing documents according to the topics is good, if you think you will use those documents to study only one topic that you have chosen in advance. However, if you want to ask different questions, it creates a mess, as you have no obvious way to retrace what you need.

The original order, as the name implies, is the one that each archive tends to have as it slowly accumulates its own records, and the archive of the Italian Minister of the Colonies was organized this way at first. However in the 1930s, as Italy reshaped its own colonial empire by brutally invading Ethiopia, also the archivists in Rome decided to restructure their paper possessions, on the basis of the topics they dealt with. While they were still underway in this process, however, the Second World War broke out: as cultural institutions normally do in times of war, collections were stored in safe places in the state they were in, while in Africa all Italian possessions were overrun by the Allies and the Ethiopian resistance. Then the Allies landed in Italy, the country surrendered, Germany invaded in its turn the parts where the Allies had not arrived yet and set up its own puppet government… by the end of 1943 there were two competing Italian states at war with each other. Each of them had, nominally, a Ministry of the Colonies, each of them wanted to keep its records, and the Fascist one transferred whatever it could to its power base in Northern Italy. It was a hasty and disastrous process: one wagon full of papers was mistakenly attached to a train headed to Germany, where it was simply lost, some other documents were destroyed while being shipped across Lake Maggiore…

In 1945 peace was restored, and whatever documents could be salvaged were slowly gathered back to Rome. Italy was forced to give up its colonies, and the relevant Ministry was closed. Its archives, now quite messy, were entrusted to a committee that was supposed to make an inventory and, while they were there, also to produce historical research on Italian colonialism. This committee was a product of the old ministry, so their description of the subject was quite sugarcoated. Moreover they also altered again the archives: after extracting the most relevant documents for study, they gathered them in a new collection, creating yet another miscellaneous record.

It was only after some time that other scholars were given access to the sources. A re-evaluation of Italian colonialism followed: the idea of a relatively benign occupation was abandoned, after it emerged that the Italians were not at all better than other colonizers: if anything, they were probably worse than average, in terms of atrocities committed and investment in local human capital. Especially the use of poisonous gas in Ethiopia, finally acknowledged by the Italian authorities in 1996, was one of the topics that arrived to the public debate. All these discussions, and the research on the topic that Italian and foreign scholars continue to do, happen also thanks to the remaining documents of the Ministry of the Colonies.

Today that archive is preserved within that of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which is housed with the rest of the ministry, in the periphery of Rome. Most of its inventories are freely accessible online (https://www.esteri.it/it/uapsds/archivio-storico-e-biblioteca/archivio-storico-diplomatico/storia-e-fondi/), and its personnel is ready to help all scholars who wants to consult these documents. However, their arrangement is now quite chaotic: there is a broad geographical division between the different Italian colonies, but there are also many other independent records which relate to all the territories. Inside each section, there is a general division on the basis of topics, but with a lot of exceptions and combinations which are apparently random. One single folder, for example (Eritrea, cronologia, pacco 542) contains information on the passage of a scientific expedition through the Eritrean territory, relations with British colonial authorities in Sudan, and the repression of a Somali rebellion. Others are registered with the scantest of indications, or contain records which are not those registered in the inventories. Whatever its problems, however, this archive continues to be invaluable, for the history of Italy and the countries it invaded.

The Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs: the entrance to the historical archives is on the left side.

References:

Anna Bertinelli – Vincenzo Pellegrini, Per la storia dell’amministrazione coloniale italiana, Milano, Giuffré, 1994

Nicola Labanca, Oltremare: storia dell’espansione coloniale italiana, Bologna, Il Mulino, 2002